- Home

- Ruth Figgest

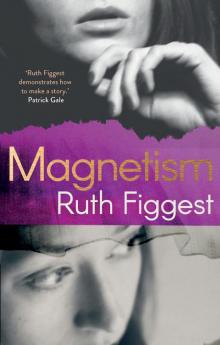

Magnetism

Magnetism Read online

Praise for Ruth Figgest

‘Ruth Figgest demonstrates how to make a story about more than one thing at once. Her astute young heroine faces the prospect of plastic surgery to render her looks more pleasing to her lovingly fault-finding mother but simultaneously arrives at a new understanding of the state of her parents’ marriage and the ambivalent purpose she has to serve within it.’

Patrick Gale

‘Ruth Figgest has a deep understanding of the human condition in all its many guises and depicts it with razorsharp accuracy. Her characters are emotionally vulnerable, self-sabotaging, and prone to exhilaratingly outrageous behaviour, but they somehow never lose our sympathy. This is psychologically acute, perceptive and witty writing that can make you laugh out loud and wince with discomfort at the same time.’

Umi Sinha

‘A thoroughly compelling read: pointed yet subtle, it skewers middle-class American foibles with biting humour and authentic compassion. Figgest’s voices are so real and tangible they leap off the page into your ears and into your bones.’

Martin Spinelli

‘Ruth Figgest has as firm and careful a grasp on the delicate texture of relationships as any writer since Henry James. This painful—and often, disconcertingly, funny—exploration of a mother and daughter’s growing apart, growing up, growing old, growing together, peels back layers of time and accretions of expectation to bare a connection harder than love and more complex than distance. It is a compelling novel.’

Claudia Gould

Magnetism

Ruth Figgest

This book is dedicated to Cara Bentham,

Kate Crouch, and Valerie’s daughter,

Jane Olsen. With love.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

1976: The Quickening

2013: The Tornado

2011: The Blind Sentinel

2007: The Cockatoo

2005: The Wind

1999: The Weasel

1999: The Mutt

1995: On Becoming a Fish

1994: Butterflies

1991: Fireworks

1988: Fireflies

1985: The Seahorse

1983: The Egg

1981: The Idea of Sushi

1980: The Kokopelli

1979: The Cockerel

1977: Big Bird

1976: Silk Worms

1975: Whispering Pines

1974: Magnetism

1973: The Armadillo

1971: The Foetal Pig

1970: Baby Bird

1969: The Wattle

1968: Wonder Woman

1964: The Stone

1961: In and Out

1959: The Lamb

2013: An Angel

2014: Prince Poopy

2015: The Bear

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

1976

The Quickening

Carl says, ‘My money’s on failed suicide.’ He rocks his chair back to lift up the front legs and balance on the back ones, just like you’re told not to do at school. I recognise that this is a skill that has taken a lot of practice to perfect. He is self-contained and whenever he speaks his voice is surprising. It’s very gentle and soothing, almost a whisper. There’s something familiar about his speech: I recognise a bit of a drawl; maybe he’s not always been from around here.

He is talking to Wilbur and they’re talking about me. Both sexes mix together in this ward and right now the three of us are sitting at the edge of the communal area. I got here first when I finished my cereal and when they finished breakfast too they came to sit either side of me. No one sits on the sofas in the morning; we will do that later. You have to make some changes just to break up the day and in the morning you need the hard seats to make you realise that yes, you are awake and yes, you are here. You are still here in this place, and you can’t leave. No one knows when they’ll be able to go home.

Wilbur scoots his chair even closer to mine and turns to study me. Wilbur has gorgeous hair, like David Cassidy. I notice how it swings forward when he moves close to me and imagine how soft it must feel when it tickles his neck. I don’t move a muscle and I do not blink as he studies my face, and his eyes drift down to my breasts, my stomach, my legs. He looks at my arms and my wrists, my hands.

He looks right in my eyes. His voice is a hiss. ‘That is by far the largest cat-e-gor-y – ’ he spaces this word out, every one of its syllables distinct and clear, his mouth movement large, as if he thinks I might possibly be deaf ‘ – and there’s nothing wrong with that, honey,’ he says. I’m keeping still as the red-hot tip of the cigarette he holds between his fingers comes closer. He strokes my face with his thumb and then he withdraws and settles back in his chair again. I can feel the trace of his hand on my skin as if it has come up in a welt.

Now Wilbur takes a deep drag of his Virginia Slim and blows the smoke out. The smoke floats up above us and it is mesmerising. He waves his hand about to shoo it away from his hair. I tip my head to watch it all disappear near the ceiling and I realise how much I need to lie down. I am as heavy as the smoke is light. The weight of my head is too much, the muscles of my lower back cannot hold my spine erect, I ache with the effort of sitting here, of being here. Of being.

Carl laughs loudly and all the tension I feel is momentarily broken. I know that he is not laughing at me, nor is he laughing at Wilbur, he is just laughing. The place is crazy and the sound he makes is deep and unbroken – not a chuckle, a real laugh – and it must be contagious because Wilbur laughs a high-pitched squeal, and I know I would like to as well, but I don’t know how to move my face to make it laugh and I cannot make a sound. I am still as the two of them laugh either side of me as if the funniest thing was on TV or something.

I’ve been told that the mirror mirror on the wall is a one-way window into the nurses’ office, but Florence, a big black woman, one of the nursing assistants, still pops her head right out of the door to see what the commotion is. She smiles when she sees the two of them laughing and Wilbur reaches around me and slaps Carl’s back. He points back to Florence and now she waves and laughs as well and goes back inside the office.

We are not allowed in our rooms during the day. On this, the fifth floor, we have to be in the communal area from six in the morning until eight in the evening and no one is ever allowed to lie down on the sofas. Everyone says it’s okay to do nothing but sit, but no one seems to understand that it’s too much even to do nothing. I want to sleep. Actually, I’ve thought about this a lot. Mashed potato is served every day for dinner and I feel like mashed potato: heavy and gloppy and inert. You have to eat something at each meal. The nurses make notes all day long and what you eat goes down on your records. You also have to stay in plain sight for at least two hours after meals. Wilbur explained to me that no one is allowed to use the bathroom for a while after eating because some people are here because they make themselves sick after meals. He told me that when I first got transferred to this floor, even though I didn’t ask, didn’t want to know and it wasn’t something I’d ever done. He said it can be quite effective but it ruins your teeth. ‘Not my bag,’ he said. He opened his mouth to run the tip of his tongue across his own teeth, so that I could see that they were white and perfect and evenly spaced, like a movie star’s. I wondered if he’d had braces.

As long as you stay on this floor, if you eat then you are allowed to wear your own clothes, and this means whatever you want, apparently. There’s a man who dresses like a woman and that’s still okay. Since I’ve been here I’ve eaten every meal, but for the last three weeks I’ve been wearing these corduroy pants and this pale yellow top, which is what I was wearing when I was admitted. Mom brought in some unde

rwear and new jeans and T-shirts for me, but I’m happy with what I’ve got on. I change my panties but the rest can be my hospital uniform, now that I’m on this floor and am allowed to wear clothes.

Mom has been here every day since I arrived, even though they wouldn’t allow her to see me for the first week when I was upstairs. My father hasn’t come. She says it upsets him too much, to think about this, that Dad has always been the sort of person to shy away from difficult things; she should know, she said. She was sorry that this was a disappointment for me, but he didn’t mean anything by it, it’s who he is, she said. That’s all, just the sort of person he is. ‘A person who finds it difficult to change,’ she said.

The new things she’s brought for me remain in the pink overnight bag under the bed in my room, along with some books she thought I might like to read: Dr Atkins’ Diet Revolution: The High Calorie Way to Stay Thin Forever; Yoga 28 Day Exercise Plan; and How to Live with Yourself. That last book has a bright red cover with a white border, like a big stop sign. I’ve put it at the bottom of the pile.

Wilbur gripes every day that all the stodge they serve up for our meals is ruining his figure. The first time he said that to me he untucked and lifted his dress shirt and stroked the flattest belly I have ever seen on anyone, man or woman. He must do a hundred sit-ups a day. ‘You know,’ he says to me now, ‘you might as well smoke. I think it’s real good that you don’t, but you might as well. You’re allowed, so I say, why ever not? Why not?’ he repeats. ‘Do you want one?’ He offers me his pack.

I don’t take it. I don’t move. I shut my eyes. I am not here.

‘She doesn’t smoke,’ Carl says. ‘Leave the kid alone.’

Now the ward door buzzer goes off and I look at the clock. It’s seven-thirty. I’ve been awake for nearly two hours. It’s half an hour since breakfast finished.

‘They’re back,’ Wilbur says. ‘Right on time. They run this place like a bus terminal. Coming and going. No peace.’

Dolly, Florence and Leanne come out of the nurses’ room. Florence starts putting out bowls and spoons and laying the places at the smallest of the three breakfast tables and then Henry comes in first, with his big clipboard, followed by four patients wearing hospital pyjamas. I don’t know the names of the two old men in the group and in fact I’ve never seen one of them before, but I know the two women: Franny and Alice.

Alice’s husband comes to see her most days. She has a beautiful face and lovely blonde hair and he sits next to her stroking it all the time he’s visiting. Wilbur says that her baby died and she killed it. I think he’s lying – they’d have put her in prison if she killed a baby – but she doesn’t stop crying even all the time her husband plays with her hair, as if she’s done something terrible, so maybe she did.

The four of them stop in a line and Leanne and Dolly go forward to guide them to the tables. Leanne is a scrawny white woman and Dolly is dark brown and plump like her name. They’re nursing assistants like Florence, but Henry is a registered nurse. I’m not sure about the others that come on duty now and then, and especially the night staff, because not everyone wears a badge, or they wear it clipped in an awkward place you don’t want to look, like on their belts dangling above their groin, or else upside down. No one has a last name on display.

The four in blue pyjamas trickle over to the tables where they sit down like obedient first graders. Florence is waiting and glops oatmeal into metal bowls from a tray and puts one in front of each of them. They’re asleep, really, even as they lift the spoons into their gaping mouths, but they chomp and chew and suck their way back to being awake.

They look like zombies and there’s something terrifying about it, but I can’t help watching. Outside, staring at other people is rude. Inside, there’s usually nothing else to do and it’s all we do at times even when there is something we could do. The open areas are littered with puzzles, magazines, decks of cards and board games, but here we kill time watching everyone else killing time.

Wilbur is watching them too. He’s pretending not to be scared by it. He says, ‘You know, almost everyone gets the ECT, in the end. Not me, mind, but I am a complicated diagnosis. Until they straighten that out, I am not going down that road. No, sir-ree. No. Don’t you think?’

Carl’s expression in return is beautifully, defiantly blank. No one could know what he was thinking and I’m pleased he doesn’t answer, but the lack of acknowledgement or agreement annoys Wilbur. He must have been a terrible gossip in normal life. Wilbur says to Carl, ‘Well, fuck you. Excuse me for trying to have a conversation,’ but he’s not really angry, he’s just desperate for something – so he wants to know what’s wrong with everyone here, but in a way that’s all, now, that any of us have to ourselves. We’re both holding out; Carl won’t tell and neither will I.

I haven’t spoken a word for at least eight weeks.

‘Fried brains or not, Franny will at least talk to me,’ Wilbur says. ‘You watch.’ He goes over to the table, squats next to her chair and strokes her head.

Franny is old, about sixty, and her grey hair is long and very frizzy. Franny and Wilbur are always so close that I wonder if they were friends from before here, or maybe they’re just good friends because they’ve both been here longer than anyone else. I wonder why she’s here, and why she’s on the list for ECT twice a week, every week, and then I wonder how long until I’ll get out, or if I’ll end up like her. I don’t know what will happen but, even though I don’t want to be like her, I don’t think I’ll ever want to leave. I can’t imagine being that old. It’s a creepy thought, she must have been my age once.

When Franny turns to look at Wilbur, she appears surprised then a couple of seconds later recognition flickers over her face. Then she smiles at him broadly, cleanly and honestly, just like a two-year-old. Wilbur turns back to us to see if we’re watching. He wants to know that we’ve registered the power that he has. He has woken Franny from sleep – brought his friend back from the dead.

‘He’s like some fairytale faggot prince,’ Carl says now, which makes me jump because I didn’t realise he might be able to read my mind.

2013

The Tornado

I am at work when the phone call comes and it takes me a minute to understand who is speaking. I finally grasp that it’s Gus, who is this ancient guy who goes to Mom’s old church and takes care of her yard. He’s phoning from Phoenix.

‘Gus,’ I say. ‘How are you?’

His voice wavers. ‘Your mother, honey. It’s bad news.’ I sit down.

When I get off the phone I go to tell my boss that I have to leave. Jerry is the head of public information and marketing. I explain that just now I had a call to say my mother has died. I tell him that my work is right up to date. I can provide him a quick handover for events and where we’ve got so far and he’ll be able to pick up on anything that might be coming up. ‘I can email you anything you need to know in my absence. But,’ I say, ‘I think I really have to get on a plane.’ I start to shake and he gets up from behind his desk and takes my arm and leads me to sit down in the space he’s vacated.

Just as I am sitting down, his secretary interrupts us. She appears surprised to see me sitting in his place behind his desk. Candy, a massive middle-aged woman – my sort of age – is wearing a sticky-out brown A-line skirt below a baggy blue turtleneck, and brown penny loafers. She is as different from spun sugar as a cactus from a dandelion and therefore, of course, her nickname is Cotton. Jerry asks Cotton to get us a coffee. He takes her to the door and intends a whisper but I can hear him tell her that my mother has passed.

By the time Cotton returns with two mugs of steaming black coffee I am unable to stop my legs from jerking up and down. ‘I’m sorry,’ I say. ‘I don’t know why I’m shaking.’

‘It’s the shock. Have a sip and take a bite of a cookie.’ She passes me a box of animal crackers. ‘Shock can kill a person,’ Cotton says, ‘And you’re way too skinny.’

Her definition of sk

inny is warped, so this is not true, but I probably do weigh near a hundred pounds less than she does. I say, ‘I’ve got reserves enough, but there’ll be stuff to do. I don’t know what to do.’

Jerry is reliably definite. ‘Yellow Pages, or the internet. Find a funeral director and he’ll walk you through it. It’s their job. They’ll know what to do and how. You don’t have to decide anything. They’re professionals. Let them do what they need to do and let it happen. Keep your head low and go with the flow.’

I’d expect nothing less from Jerry. He is what people call a born leader, a very likeable guy. This is exactly why he got this job. He sounds decisive and confident but he never makes a decision he can be held accountable for and everyone else does everything. He doesn’t actually do a thing.

I thank him for the advice and then Cotton kindly arranges the tickets and a cab and I phone Gus back to tell him when I’ll be arriving.

I go to the airport via my apartment and I collect spare contact lenses, a pair of glasses, and a change of clothes. I don’t have to take much. I can’t really think about what to pack anyway. The driver waits for me and, though there is traffic, we get to the airport in time for me to check in and sit and wait until it’s time to board.

I look around at the people waiting, like me, at the airline gate. There are people travelling in pairs talking to each other, others travelling alone, reading magazines or staring out the window at the parked planes. Perhaps some are afraid of flying, some are tired and going home to see their families, instead of going somewhere they don’t live and facing something unexpected. There’s a woman who is around my mother’s age. She looks perfectly healthy, and, the last time I saw her, Mom did as well. People in their seventies probably die all the time, but plenty of them don’t. I’d put money on this woman living at least another ten years. She is holding a magazine. Her reading glasses are propped on her nose but she’s not looking at the Reader’s Digest, she’s looking around her at the other passengers. Our eyes meet momentarily until I look away.

Magnetism

Magnetism